On Mentoring and Being Mentored

22 Apr 2018

Background

Why would I choose to write about mentoring?

I guess it’s a topic that I’ve pondered over the years, ever since my first job out of university. During the couple of years I worked at TNT I didn’t benefit from any formal mentoring. However, when I think of who had a big impact on my learning on the job, there were certainly a couple of people who immediately come to mind.

But it was when I arrived at IBM that I was struck by the fact that everyone in the team was allocated an adviser. So I knew that, if I ever had any questions about anything, I could approach Rod, my adviser. I knew he had a wealth of experience and found his help invaluable. What impressed me even more was the fact that the company considered mentoring important enough to implement such a scheme.

That was back in 1986. Fast forward to 2018 and I’m in a very different situation, keenly aware of the need for young programmers with whom I work to have good mentoring.

So, several weeks ago, at RubyConf AU, when Alaina Kafkes challenged those in the audience of her talk about Tackling Technical Writing to publicly commit to writing about a particular topic, my response was:

And given that Sean was generous enough to say that he’d read what I had to say on this topic, it’s only fair that I put words to the screen and share my thoughts.

Mentoring Others

Meaning

Before I dive into my thoughts about mentoring others, I think it pays to pause and consider the meaning of the word mentor. The dictionary on my Mac defines a mentor as:

An experienced and trusted adviser.

Now that we have that definition out of the way, let’s consider what it takes, in my experience, to be a good experienced and trusted adviser.

Patience

One thing that I consider to be vital when mentoring is to be aware of the right time to offer advice. As a parent I’ve come to learn that one has to be patient and wait for the right moment. Or, to borrow from another context, I love the quote from Jack Gibson, the Rugby League coach, who said:

“A good coach thinks twice and says nothing.”

In other words, try to cultivate a sense of recognising moments when your colleague is ready for advice. It’s important to allow them the time and space to try to figure things out for themselves. You’ll usually know when they’re ready for your advice. They’ll ask you a question!

On the other hand, there will be times when your colleague could use some advice but doesn’t ask for it. So make it clear that he or she is welcome to ask questions about anything.

And then wait.

Provide a framework

It’s one thing to encourage your mentee to ask questions. However, to provide them with the basis to ask good questions that will help them learn, a framework will help.

What do I mean by a framework?

To begin with, something that provides structured learning. To be fair to your colleague, they’ll need training to help them be most effective at their work. Appropriate training will help the developer feel that they have ascended to a new level and give them confidence. That confidence should translate into a greater preparedness to attempt new tasks and, importantly, spark questions that will further improve understanding.

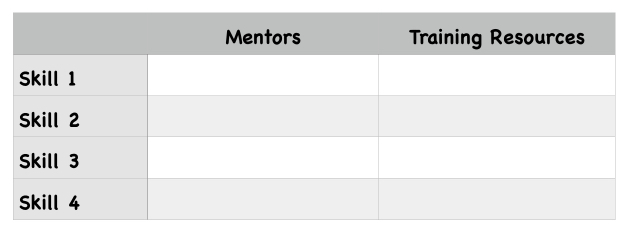

Also, it’s likely that different members of the team will have different strengths. Part of my envisioned framework is a skills matrix. For each skill there will be specialist mentors as well as a set of training resources.

In the early stages of implementing a mentoring program for a team, there may be a few gaps and imbalances in this matrix. For example, a skill that is important to the team may be Ruby Performance Optimisation. However, there may be nobody in the team that has sufficient strength in that skill to mentor others in the team. A next step to start filling that gap may be to identify some training resources, allocate one developer to complete that training and then become the mentor for that skill.

Continuing in this way, the skills matrix should start to take better shape. The aim should be to manage its evolution so that there is an even spread of mentors across the skills that are important to the team.

Everyone is different

Naturally we all differ. We gravitate towards different skills. We think differently. We have different needs.

So, in my perfect mentoring world, the needs of every individual should be provided for by a mentoring program that is fine-tuned and continuously adapted for that person. In practice this may not always be possible to the ideal degree. However, I think it is worth striving for.

Consider the other’s viewpoint

Perhaps this point is obvious.

However, I think it’s worth stating explicitly. Whether it’s during the process of creating and maintaining a mentoring framework, or in the act of mentoring, it pays to put oneself in the shoes of the other.

What are they keen to learn? What do they think they need to learn in order to do their job better? What do you think they need to learn in order to do their job better?

It pays to explore these questions in an open manner.

Pairing

Working as a pair, where one developer is a mentor and the other is more focussed on learning, can be an effective way of enabling a junior developer to grow. Whilst in general a more typical pair programming approach would involve two developers who are on a more or less even footing, switching the driver and navigator roles, a mentor/mentee pair offers an effective learning experience.

Having said that, there is a caveat. When there is a marked difference in skill levels, pair programming can be intensive and tiring, especially for the mentor. So it is important to be aware of this and provide sufficient breaks between pairing sessions. Ideally, as Ryan Bigg emphasised in his talk about hiring juniors at the recent RubyConf AU, a task that can be completed within two to three days is a good choice for this style of pairing.

One-on-one

As I alluded to previously, it’s important to consider the point of view of the person you are teaching. It’s not going to be surprising for them to feel self-conscious, even overwhelmed at times. So, as a caring mentor, ensure that there will be regular opportunities to catch up with your colleague in a one-on-one context.

I’m reminded about a coaching context again. When you’re coaching a team or a group, it pays to offer praise in public. It makes the recipient feel good. A little bit of an ego boost goes a long way.

On the other hand, if there’s a need for some constructive criticism, this is obviously best given in private. Nobody likes to be given negative feedback in front of their peers.

Being Mentored

Identifying mentors

When you’re a younger worker, learning your craft, it shouldn’t be difficult to identify trusted advisers. However, as one grows older, mentors aren’t as easy to identify. I know that from experience.

And I have to admit that in recent years I have struggled to find a single person who I can look to for advice as my professional advisor. When I consider my experience over the last decade or so, it leads me to reflect on the various needs I have for advice.

Perhaps, in my case, as an older, experienced IT professional working within a small group of developers, I need to be more flexible in the way I seek advice.

Relevant experience

My need for advice may stem from different sources.

In a more general, career sense, given that I’m closer to 60 years of age than 50, it’s likely that I need to look broadly to find someone who can give me appropriate career advice. Or, perhaps, I need to consider my own counsel. However, having said that, I think that’s probably a lazy response. Even though it will take more effort, I think it’s worth my while to keep searching for someone who I feel I can trust to give me good advice about how to approach the closing decade of my career as a software developer. Such an advisor will most likely outside my usual circle of professional colleagues.

Then again, my need for advice in a professional context may result from other sources. Perhaps I will need specific technical advice?

Younger mentors?

It shouldn’t be surprising in the context of professional software development as a senior practitioner to encounter situations where younger colleagues have greater expertise in specific disciplines and technologies. One only has to think of the latest JavaScript framework to develop a keen appreciation!

I’m certainly not too proud to seek advice from younger developers about technologies such as React and Webpack, for example.

So I guess, in essence, I think I should be prepared to seek and accept advice from different mentors for different topics.

Getting specific advice

At any stage in one’s career I think it makes sense to be flexible about seeking specific advice. Obviously some people are going to have greater expertise in particular topics than others.

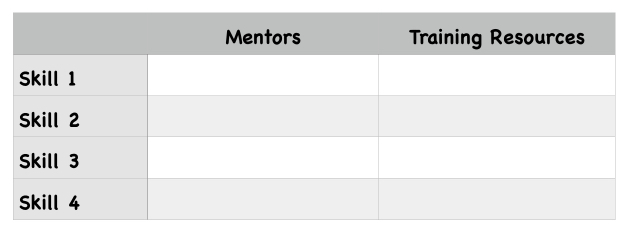

In my own case, I think it definitely makes sense to think of seeking advice in specific terms. Who has the best advice to offer about specific skills?

So, when I’m looking to be mentored, it probably makes sense to consider the same matrix that I proposed earlier.

Wrapping up

One of the things I love about working as a software developer is the opportunity for learning and teaching.

It’s pretty rare to go through a career in software development without working as part of a development team. Every member of a team needs mentoring and most will be in a position to also help others in their team. Even if you spend much of your career as a freelance developer you will benefit from and be in a position to provide mentoring.

I hope this post has stimulated your thinking in some way about mentoring.

After all, when you think about it, it’s a two-way street. There are obviously going to be times when you need advice. So, it seems only fair that you be prepared to offer advice as well!

Other posts

Previous post: Moving on to Birdsnest

More recently: Remembering Jerry Weinberg